I love academia as much as the next guy. (Ok, most likely a lot more than the next guy), but even I have to tip my hat to and scowl at K. Levinson, who led the “Psychology of Anime” panel at Zenkaikon 2009. A published student and teacher of psychology, Levinson decided to base the panel on the cognitive approach and certainly cannot be accused of talking down to the crowd. Having not taken a bit of psychology since I was in college myself, I found my dying brain cells barely an adequate bridge to traverse the topics of why people love anime, what the nature of their attraction to it is, and what the reasons behind the artists’ choices when developing series are.

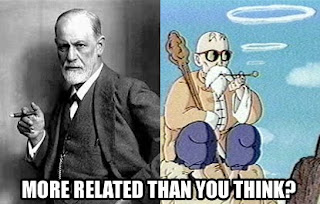

Almost any time anyone mentions psychology, the first figure to come to mind is Dr. Sigmund Freud. So what would the father of psychoanalysis say about our particular branch of fandom? Given his life drive theory, it would be anime’s aggressiveness and sexuality that keep otaku buying DVDs en masse. Big guns, big…girls. Very simple. Continuing along the timeline of psychological development, theories get a little more complicated.

Social psychology, or how people interact with other people and within groups, was our next area of examination. Basically, this field would theorize that anime viewers watch to observe relationships. I’m not only talking your typical boy/girl doting upon girl/boy (or any combination thereof), but relationships between government and people, individuals to their situations, etc. It is a form of vicarious living. But viewers don’t want to be the characters. Instead, they feel an association or desire for particular exhibited qualities. Keep this in mind when we visit Gestalt psychology.

Between here and there, however, was Abraham Maslow and his theory of the hierarchy of human needs: physiological, safety, love/belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. Answers to what portions of the needs pyramid anime could satisfy included partial or entire levels of safety, love/belonging, and esteem. But how? The innate morality and sense of family in most anime would take care of at least relaying a vision of a comprehensible and achievable level of safety; vicarious themes of friendship, intimacy, and family take viewers into a sense of love/belonging; and contrasts between characters and viewers can instill a sense of confidence or bolster their self-esteem.

In Gestalt psychology, everything is analyzed from top to bottom – as a whole first and then by parts. Followers of this branch of psychology would believe anime viewers just don’t see the components – characters, plot, setting, animation style, music – but experience the whole first before breaking it down into what appeals to them. After viewers identify enjoyable wholes (genres), elements thereof can then be further broken down, and components of those elements micro-analyzed, etc. What makes this theory so plausible is the inherent oversimplification aspect of anime. It is the driving force behind the medium’s accelerated growth, because the simpler the whole, the easier to access, identify, and break down.

Lastly, the (fraternal) twin cities of determinism and relativism respectively state that the way people speak the language is the way they view the world and that the way people perceive things determines their language. Aspects of both arguments are most prevalent in the great sub/dub debate, which would point out missed jokes and incorrect meanings via translation. Symbolic interactions determine how we interpret, so that is why dubs should appeal to US viewers in a different way that subs do: jokes and phraseology are often tweaked for the native language instead of being verbatim translations that go over the proverbial heads of foreign audiences. Also related to this theory is the concept that anyone’s first viewing of anime is relativistic. Viewers start to form templates of new material’s form from their initial viewing, relying upon that experience as a control in an experiment. Continued watching becomes deterministic, because viewers are familiar with the form and can start to use their learned language to compare it against a familiar form.

I hope those views gave you something to chew on. There was a lot more name-dropping and psychological mumbo-jumbo, but I think Wikipedia charges by the link, and, if your head is anything like mine, it’s probably screaming out for some aspirin right about now. Take some, and next time you sit down with a favorite series, think, if only for a moment: what specifically drew you to it, how does it make you feel, and how do you use it? The answers just might surprise you.

Ani-Gamers blogger Ink checked out a whole bunch of the panels and events at Zenkaikon 2009. For more coverage, keep your eyes on our Zenkaikon 09 label!