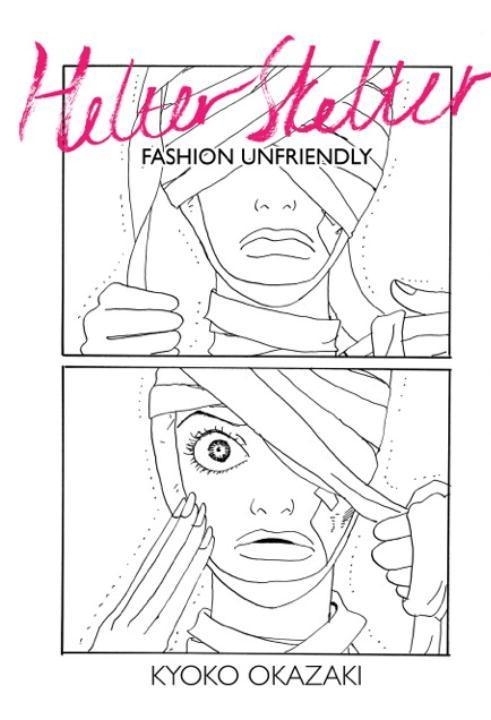

Helter Skelter – Fashion Unfriendly

Coming down fast but don't let me break you

Serialized in 1995 in Japan via Feel Young Magazine (a fitting magazine title for the story contained therein), Helter Skelter speaks just as strongly on the subjects of fashion and celebrity in 2014 as it probably did upon its original publication. That’s depressing, since it means that tempting, impossible promises of perfect bodies are still the bread and butter of the fashion industry. Kyoko Okazaki’s unflinching critique of this world cuts deep yet mostly avoids the sort of pointed moralizing you might expect from a story about the subject.

Serialized in 1995 in Japan via Feel Young Magazine (a fitting magazine title for the story contained therein), Helter Skelter speaks just as strongly on the subjects of fashion and celebrity in 2014 as it probably did upon its original publication. That’s depressing, since it means that tempting, impossible promises of perfect bodies are still the bread and butter of the fashion industry. Kyoko Okazaki’s unflinching critique of this world cuts deep yet mostly avoids the sort of pointed moralizing you might expect from a story about the subject.

Liliko is beautiful from head to toe, with shockingly European features, an alluring figure, and an enigmatic personality. As a supermodel, she finds her way into fashion, acting, singing, and more — she’s a true celebrity in that her greatest asset is simply her own brand. But Liliko is a fake. As the president of her agency muses early in the book, “the only parts she’s kept are her bones, eyeballs, nails, hair, ears, and twat.” The rest, including her skin and fat, has been destroyed then reconstructed through a gruesome plastic surgery process, and is maintained thanks to a dizzying cocktail of drugs. Liliko’s career is suspended by tenuous strings, existing only with the help of a dangerous, secretive lifestyle of heavy drugging and regular plastic surgery checkups. But by the end of the first chapter, her skin begins to bruise. The mask is falling off.

Soon, Liliko’s life spirals out of control, dragging her besotted, bisexual manager and her boyfriend into the mix. Meanwhile, a detective takes an interest in Liliko and begins to connect her to his investigation of the underground clinic she patronizes.

Okazaki pulls no punches here. It takes only 10 pages to get to full-frontal nudity, and Liliko’s lifestyle is portrayed as monstrous, not enviable. She spits water in the face of her manager, verbally degrades everyone around her, then turns around and sweetly demands that they make themselves available to her, professionally and sexually. Her arrogance might be abrasive if Okazaki wasn’t so masterful at drawing you into her world, making the distressed, nearly bipolar Liliko out to be a victim of herself.

And victims abound, though there are no clear culprits. Is the head of Liliko’s agency, who discovered the then-overweight woman and reconstructed her, to blame? Do the stylists, hairdressers, and managers who take Liliko’s arrogant verbal lashings then tell her how great she is contribute to that very same arrogance? What of the girls who eat up the tabloid celebrity gossip, wanting nothing more than to be just like Liliko and proving their dedication by buying into a broken system? Okazaki makes clear that, in the end, we are all to blame. The destructive nature of celebrity is a collaborative project, an ouroboros of unfulfilled dreams wherein the victims become the victimizers. There is no better example than the head of the agency, whom Liliko refers to as “Mama” (her real mother is never shown), and who “created” Liliko in her own image to live her youth anew.

All of this pain is depicted with stark, scratchy line art. Perhaps most impressive is Okazaki’s versatility; she is able to depict a gorgeous glamor shot followed by a minimalistic one-panel visual gag, and each has its own distinct personality. When Helter Skelter veers toward the cartoonish, the designs sometimes resemble the almond eyes and strange faces of Natsume Ono, a more contemporary artist who is undoubtedly influenced by Okazaki. Unfortunately, those faces can be difficult to tell apart — there are three different characters with similar short black hair and earrings (two women and one man).

Helter Skelter floats along in surreal, druggy blurs of emotions and memories but maintains a strong sense of gravity. That’s to say that things fall down and accelerate, and I dare anyone to resist reading the second half of this book, as Liliko’s spiral of despair intensifies, in anything except a single sitting.

Okazaki is a pioneer of modern josei (women’s) manga, and it’s easy to see why. This is no girlish shojo manga, but it’s also not the hard-boiled badassery of seinen. The so-called “mother of josei” (or at least one of them) hits hard and fast with characters who alternate between being tragic and detestable. Like reading the celebrity gossip pages, Helter Skelter will leave you slightly perplexed, supremely disgusted, and more than a little entertained. As long as you come away with number 3, though, that’s mission accomplished as far as the mechanics of celebrity are concerned. The show must go on.